The Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara is the remainder of a once powerful empire of Kitara. At the hight of its glory, the empire included present day Masindi, Hoima, Kibaale, Kabarole and Kasese districts; also parts of present day Western Kenya, Northern Tanzania and Eastern Congo. That Bunyoro-Kitara is only a skeleton of what it used to be is an absolute truth to which History can testify.

One may ask how a mighty empire, like Kitara, became whittled away to the present underpopulated and underdeveloped kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara. This is the result of many years of orchestrated, intentional and malicious marginalization, dating back to the early colonial days. The people of Bunyoro, under the reign of the mighty king Cwa II Kabalega, resisted colonial domination. Kabalega, and his well-trained army of “Abarusuura” (soldiers), put his own life on the line by mounting a fierce, bloody resistance against the powers of colonialization. On April 9th, 1899, Kabalega was captured by the invading colonial forces and was sent into exile on the Seychelles Islands.

With the capture of Kabalega, the Banyoro were left in a weakened military, social and economic state, from which they have never fully recovered. Colonial persecution of the Banyoro did not stop at Kabalega’s ignominious capture and exile. Acts of systematic genocide continued to be carried out against the Banyoro, by the colonialists and other foreign invaders.

Colonial efforts to reduce Bunyoro to a non-entity were numerous, and continued over a long period of time. They included invasions where masses were massacred; depopulating large tracts of fertile land and setting them aside as game reserves; enforcing the growing of crops like tobacco and cotton at the expense of food crops; sanctioning looting and pilaging of villages by invading forces, importation killer diseases like syphilis that grew to epidemic proportions; and the list goes on.

Details of the horrific, genocidal acts against the Banyoro are well documented in “Breaking Chains of Poverty”, published by the Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom Advocacy Publications; authored by the Hon. Yolamu Ndoleriire Nsamba, Principal Private Secretary to H.M Solomon Gafabusa Iguru I, Omukama of Bunyoro-Kitara. This book is a “must read” for anyone interested in the History and welfare of Bunyoro-Kitara. It enumerates Historical events, plus practices, past and present, that made Bunyoro-Kitara “a kingdom bonded in chains of poverty”.

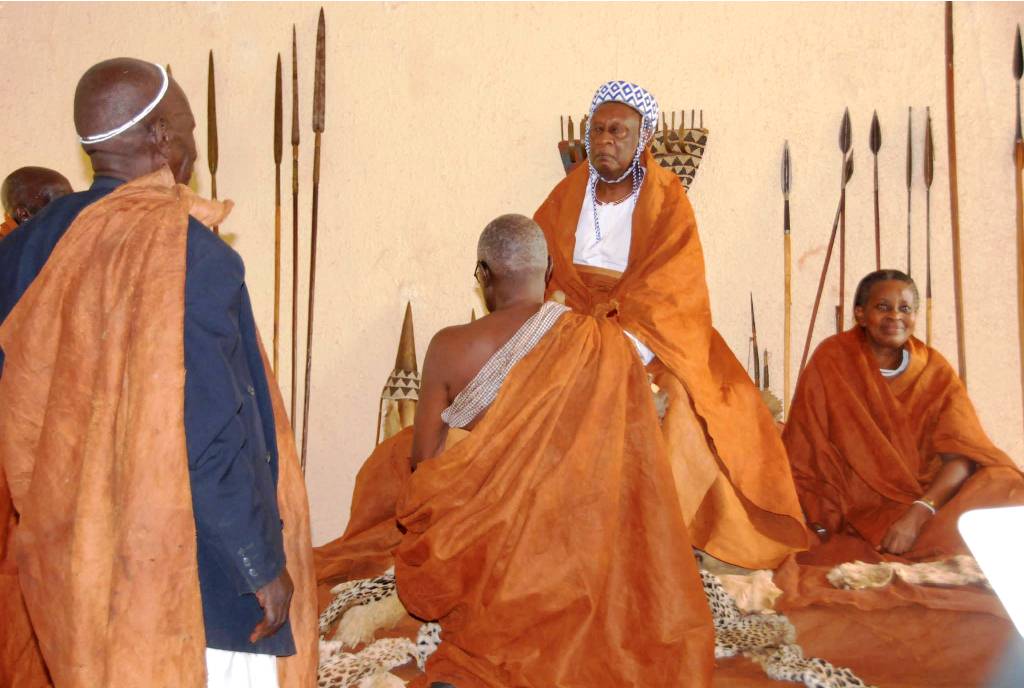

Bunyoro Kingdom was one of the most powerful kingdoms in East Africa from 13th century to the 19th century. It is ruled by the Omukama of Bunyoro. The current ruler is Solomon Iguru I, the 27th Omukama (king) of Bunyoro-Kitara.

The people of Bunyoro are also known as Nyoro or Banyoro (singular: Munyoro) (Banyoro means “People of Bunyoro”); the language spoken is Nyoro (also known as Runyoro). In the past, the traditional economy revolved around big game hunting of elephants, lions, leopards, and crocodiles. Today, the Banyoro are now agriculturalists who cultivate bananas, millet, cassava, yams, cotton, tobacco, coffee, and rice. The people are primarily Christian.

Omukama of Bunyoro is the title given to rulers of the central African kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara. The kingdom lasted as an independent state from the 16th to the 19th century. The Omukama of Bunyoro remains an important figure in Ugandan politics, especially among the Banyoro people of whom he is the titular head.

The Royal Palace, called Karuziika Palace, is located in Hoima. The current Omukama is Solomon Iguru I and his wife is the Queen or Omugo Margaret Karunga.

As a cultural head, the King is assisted by his Principal Private Secretary, a Cabinet of 21 Ministers and a Orukurato (Parliament).

History of Bunyoro

The kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara was established following the collapse of the Empire of Kitara in the 16th century. The founders of Kitara were known as the Abatembuzi, a people who were later succeeded by the Abachwezi.

At its height, Bunyoro-Kitara controlled almost the entire region between Lake Victoria, Lake Edward, and Lake Albert. One of many small states in the Great Lakes region the earliest stories of the kingdom having great power comes from the Rwanda area where there are tales of the Banyoro raiding the region under a prince named Cwa around 1520. The power of Bunyoro then faded until the mid-seventeenth century when a long period of expansion began, with the empire dominating the region by the early eighteenth century.

Bunyoro rose to power and controlled a number of the holiest shrines in the region, together with the lucrative Kibiro saltworks of Lake Albert; having the highest quality of metallurgy in the region made it the strongest military and economic power in the Great Lakes area.

Decline of Bunyoro Kingdom:

Bunyoro began to decline in the late eighteenth century due to internal divisions. Buganda seized the Kooki and Buddu regions from Bunyoro at the end of the century. In the 1830s, the large province of Toro separated, claiming much of the lucrative salt works. To the south Rwanda and Ankole were both growing rapidly, taking over some of the smaller kingdoms that had been Bunyoro’s vassals.

Thus by the mid-nineteenth century Bunyoro (also known as Unyoro at the time) was a far smaller state, though it was still wealthy due to the income generated from controlling the lucrative trade routes over Lake Victoria and linking to the coast of the Indian Ocean. In particular, Bunyoro benefited from the trade in ivory. Due to the volatile nature of the ivory trade, an armed struggle manifested between the Baganda and the Banyoro. As a result the capital was moved from Masindi to the less vulnerable Mparo. Following the death of Omakuma Kyebambe III, the region experienced a period of political instability where two kings ruled in a volatile political environment.

In July 1890 an agreement was settled whereby the entire region north of Lake Victoria was given to Great Britain. In 1894 Great Britain declared the region its protectorate. In alliance with Buganda, King Kabarega of Bunyoro resisted the efforts of Great Britain, aiming to take control of the kingdom. However, in 1899 Kaberega was captured and exiled to the Seychelles and Bunyoro was subsequently annexed to the British Empire. Because of Bunyoro’s resistance to the British, a portion of the Bunyoro kingdom’s territory was given to Buganda and Toro.

The country was put under the governance of Bugandan administrators. The Banyoro revolted in 1907; the revolt was put down, and relations improved somewhat. After the region remained loyal to Great Britain in World War I a new agreement was made in 1934 giving the region more autonomy. Bunyoro remains as one of the four constituent kingdoms of Uganda, along with Buganda, Busoga and Toro.

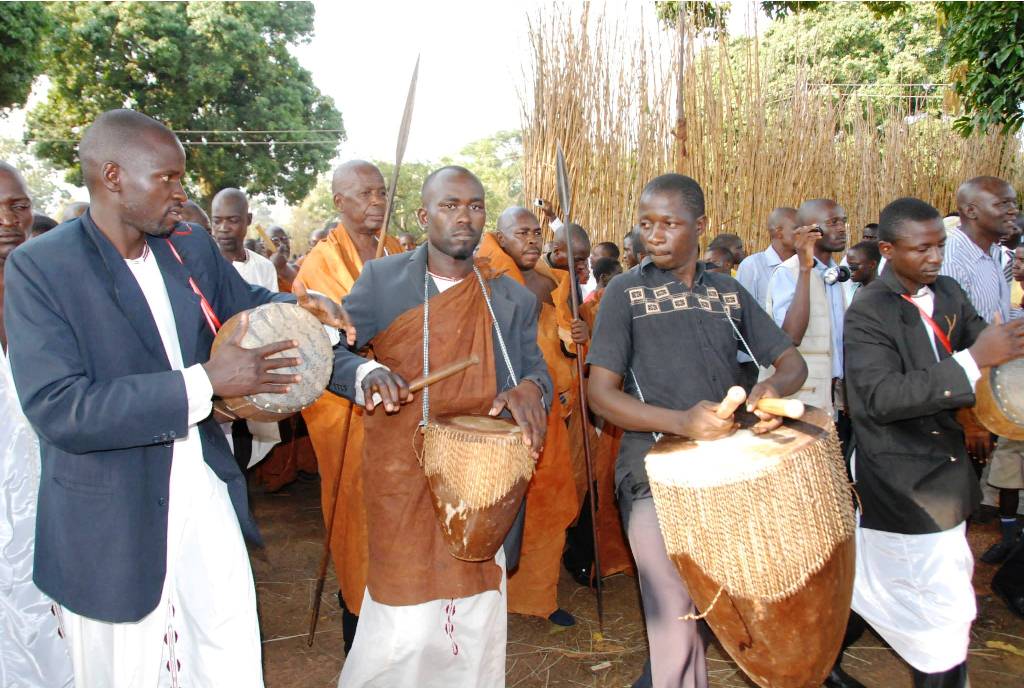

Traditions of Bunyoro

Relations

The Banyoro were traditionally a polygamous people when they could afford it. Many marriages did not last and it was quite common to be divorced. Due to this, payment to the girl’s family was not normally given until after several years of marriage. Premarital sex was also very common.

All families were ruled by the eldest man of the family (Called Nyineka), and the village was run by a specially elected elder who was chosen by all the elders in the village. He was known as a mukuru w’omugongo.

Birth

A few months after birth, the baby would be given a name. This was normally done by a close relative, but the father always had the final saying. Two names are given: a personal name, and a traditional Mpako name. The names were often related to specific features on the child, special circumstances around the birth of the child or as a way to honor a former family member. Most of the names are actual words of the Nyoro language.

Death

Death was almost always believed to be the work of evil magic, ghosts, or similar. Gossiping was believed to magically affect or harm people. Death was viewed as being a real being. When a person died, the oldest woman of the household would clean the body, cut the hair and beard, and close the eyes of the departed. The body was left for viewing and the women and children were allowed to cry/weep, but the men were not. In case the dead was the head of the household, a mixture of grain (called ensigosigo) was put in his hand, and his children had to take a small part of the grain and eat it – thus passing on his (magical) powers.

After one or two days, the body would be wrapped in cloth and a series of rites would be carried out. The following rites are only for heads of family:

- The nephew must take down the central pole of the hut and throw it in the middle of the compound

- The nephew would also take the bow and eating-bowl of the departed and throw it with the pole

- The fireplace in the hut would be extinguished

- A banana plant from the family plantation and a pot of water was also added to the pile

- The family rooster had to be caught and killed

- The main bull of the family’s cattle had to be prevented from mating during the mourning by castration

- After four days of mourning, the bull would be killed and eaten, thus ending the period of mourning

- The house of the departed would not be used again

The burial would not be done in the middle of the day, as it was considered dangerous for the sun to shine directly into the grave. As the body was carried to the grave the women were required to moderate their weeping, and it was forbidden to weep at the grave. Also pregnant women were banned from participating in the funeral as it was believed the negative magical forces related to burial would be too strong for the unborn child to survive. After the burial the family would cut some of their hair off and put it onto the grave. After the burial, all participants washed themselves thoroughly, as it was believed that the negative magical forces could harm crops.

If the departed had a grudge or other unfinished business with another family, his mouth and anus would be stuffed with clay, to prevent the ghost from haunting.