“Umukhasi umutuufu amanya inda yo museetsa” (A proper woman knows the husband’s stomach)~Bagisu Proverb.

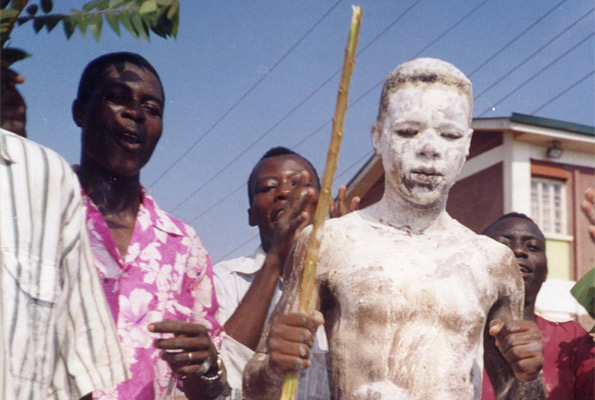

Bagisu (Bamasaaba) people: Imbalu candidates dance the Kadoodi dance at Mutoto Cultural Grounds outside Mbale town. Smeared with flour and decorated with traditional beads and bungles, the circumcision candidates dance in preparation for circumcision

The Bagisu or Gisu also known as Gishu, Bagishu, Masaba or Sokwia are people of the Bantu family who live along the slopes of Mount Elgon (also called Mount Masaba) in Mbale District eastern Uganda.

A person of Bagisu tribe is called Mugisu and everything associated with the Bagisu including their culture, tradition, values and property are also known as Kigisu. As such, one can talk of Kigisu music, Kigisu dances or kigisu culture. Further, the generic term Gisu (Gishu) has been used by scholars like Victor Turner (1969, 1973) and Suzette Heald (1982) to refer to the Bagisu people, their region, language, or culture.

As such, one can talk of the Gisu while referring to the Bagisu people or something that belongs to them. However, the Bagisu do not refer to themselves or what belongs to them as the Gisu (Gishu).

The Bagisu are known for the fearsome aggressiveness and strength by their neighbours in Uganda and Kenya whilst the world know the Bagisu people for their unique Mbalu circumcision rituals. Bagisu people take serious circumcision issues serious and any man who is uncircumcised would not be allowed to marry Bagisu woman and Bagisu woman well imbibed with Kigisu culture will never allow an uncircumcised man to penetrate her.

Imbalu circumcision rituals among the Bagisu aim at strengthening cultural continuity by enhancing the passing over of cultural responsibilities and ideologies from older generations to young ones.

As Khamalwa (2004) has also stressed, imbalu circumcision rituals construct the Bagisu identity by making them stand out as a race of “men” (basani) as opposed to other un-circumcising tribes whom the Bagisu consider as boys (basinde) (see also Heald, 1982). Indeed, one graduates into a “man” and become considered responsible and indeed a “real” Mugisu through circumcision. The women’s “true” identity is also defined by marrying a “real” man, one who is circumcised.

Bagisu boy after circumcision (Mbalu) rituals

Today, the number of Masaaba speakers is around 1,120,000 with an ethnic population of 953,936; the area is the most densely populated region of the country with 250 people per sq. kilometer. However, during the time of colonial rule, the tribe had a population of roughly two thousand.

The tribe was divided into clans—two or three around Mbale with the rest scattered around the slopes of Mt. Elgon. The clans were made up of villages containing ten homes, although this number occasionally reached forty.

In fact, the original name of the Bagisu is Bamasaba, which means “that of the Masaba origin”. According to Khamalwa (2004: 20), the name Bugisu is recent and traces it to the late nineteenth century when the British colonialists came to Uganda.

According to Khamalwa, the name Bugisu is associated with Mwambu, the eldest son of Masaba. According to a legend, Mwambu, who used to look after his father’s cattle, was attacked by the Masaai from Kenya. The Masaai took all the cattle he was herding. Mwambu is said to have raised an alarm for help but as his clansmen mobilised to come to his rescue, he followed the raiders single-handedly and caught up with them.

The Masaai were shocked with Mwambu’s courage and handed over all the cattle they had raided including an extra bull (known in the Masai language as ingisu) as a symbol of Mwambu’s bravery. When Mwambu’s father heard about the ordeal, he was so shocked that he gave Mwambu a nickname of Mugisu.

However, when the British sent Semei Kakungulu as their representative to “pacify” the eastern part of Uganda including the Mount Elgon region, he was fascinated by people who spoke a language similar to his own. When some local chiefs recounted the above legend,Kakungulu renamed the Bamasaba, the Bagisu.

Location

Generally, Bugisu stay on a mountainous region, a view evidenced by the presence of the towering Mount Elgon ranges a volcano located in Mbale District of Eastern Uganda. This area is well irrigated and contains some of the most fertile soils in the country, allowing the tribe to become dominant in agriculture.The highest point on these ranges goes as high as 8000ft while the low ones go as low as 4000ft above sea level (Khamalwa, 2004: 19).

Interwoven with the hills, caves and gorges are rivers like Manafwa, Sorokho and Lwakhakaha, with countless tributaries where imbalu candidates perform the ritual of washing their penises before proceeding for pen surgery. In the areas neighboring River Lwakhakha, imbalu candidates are taken very early in the morning to the river in order to make their muscles numb.

Language

Bagisu speak Lugisu, sometimes called Lumasaba which belongs to Niger-Congo language family. Like other Bantu languages, Lugisu has multiple dialects. While Ludadiri is a Lugisu dialect spoken by the Bagisu from the north, Lubuuya is the Lugisu dialect spoken in south Bugisu.

Further, the Bagisu who live near the Babukusu of western Kenya have the influence of Lubukusu, the language of Babukusu. And yet, the Bagisu who live in Central Bugisu speak a Lugisu dialect influenced by languages including Luganda, Lusoga, Lusamia and Lunyoli.

Bagisu dancers from Sippi Falls,Mount Elgon,Uganda

Origin/history

Wangusa (1987), who is a novelist and literature scholar, recounts that the first man among the Bagisu was called Mundu. Together with his wife Seera, Mundu emerged from a hole on top of Mount Elgon (Mount Masaba). They produced two sons- Masaba and Kundu, the former being a hunter while the latter a herdsman. According to Wangusa, Kundu left the Mount Elgon while Masaba stayed and brought imbalu circumcision rituals to the Bagisu.

Wangusa writes that:

“Kundu, who, standing upon the mountain one day when the sky was unusually

clear, saw a lake on the horizon in the direction of the setting sun. And

yearning to go and find out the secret of the lake, [Kundu] journeyed many, many days and nights till he got lost, never to return.

Travellers in subsequent generations [told] the stories of a man called Kundu, later known as Kintu, who came from the mountain of the heavens, mu ggulu, and alighting upon the far side of lake Nabulolo, gradually subdued his neighbours and became the founder of a still-surviving line of heroic kings[.] … [Kintu was] … the father of a prodigious people, whose native language was incredibly akin to that of the far-removed Mountain of the Sun, inhabited by the great- grandchildren of Masaaba the elder (1987: 79).”

Khamalwa (2004) narrates that Kundu, whose name later changed to Kintu, moved and settled in Buganda. After overthrowing the Buganda king, Kintu became their king. Indeed, scholars who have written about the Baganda correlate Khamalwa’s view that their first king Kintu, might have come from the Mount Elgon region in Bugisu. Sylvia Nannyonga- Tamusuza, for example, stresses that the theories about the origin of Buganda assert that Buganda was founded by Kintu.

She says that one of these theories “relate to Kintu as a foreigner who came from eastern Uganda in search of greener pastures for his cow … [H]e reached Muwawa (which later became the core of Buganda) [and settled]” (2005: 9).

Another story, as presented by Naleera argues that Kundu disappeared from the Mount Elgon ranges because he feared to be circumcised. Naleera writes that after witnessing the circumcision of Masaba, his elder brother, Kundu was so terrified that he moved westwards and never came back (2003:18-19).

Despite the fact that scholars have not articulated whether Masaba was circumcised before or after Kundu had moved away from his father’s household, they agree that imbalu circumcision rituals among the Bagisu were introduced by Masaba.

According to Khamalwa, as Masaba went on with his hunting expeditions in the Mount Elgon forest, he met a Kelenjin girl called Nabarwa. Nabarwa fascinated Masaba so much that he proposed marriage to her. Inspite of the fact that Nabarwa had been circumcised and Masaba was not, she agreed to Masaba’s marriage proposal. And since it was an abomination for Nabarwa to marry an uncircumcised man, she proposed circumcision to Masaba.

After consenting, Masaba was circumcised and was married to Nabarwa. Masaba and Nabarwa produced three sons– Mwambu, Wanale and Mubuya– and one daughter, Nakuti. Mwambu settled in the north of Bugisu and became the ancestor of the Bagisu called Badadiri. Wanale, who settled in the central, is the ancestor of the Bagisu living in central Bugisu and Mubuya moved to the south and became the ancestor of the clans there

The Bagisu are believed to have separated from the Bukusu sometime in the 19th century. The tradition claiming that they have always lived where they are throughout history is not fashionable. The earliest immigrants into Bugisu area are believed to have moved into the Mt. Elgon area during the 16th century from the eastern plains.

Mount Elgon park,Uganda

Their earliest home is said to have been in the Uasin Gishu plateau of Kenya. They seem to have been an end product of the mixing of peoples of different origins and cultures, but since their language is Bantu, their predecessors should have been Bantu speakers as well.

Economy

Like many Bantu communities, the Bagisu are agriculturalists. Those who stay as far as 5000ft above sea-level grow Arabica coffee, the biggest portion of it being sold to Bugisu Co-operative Union (BCU) though other companies dealing in coffee also exist. On the other hand, cotton is grown in the lower plains extending as low as 4000ft above sea level. Tobacco is another cash crop grown by a small proportion of the population.

Much as bananas are grown primarily for food, the Bagisu also sell them to supplement the income earned from coffee, cotton and tobacco. In addition, the Bagisu grow maize, beans, millet, sorghum, yams and cassava. During unfavourable climatic conditions, the Bagisu acquire millet and other foodstuffs from the Itesots, Banyoli, Jopadhola, Bagwere and Sabinys which they use in the performance of imbalu circumcision rituals.

The Bagisu also engage in business with their neighbours. Among the items traded in include food, sugar, salt, soap, cattle and musical instruments.

Food storage: The millet and corn, after drying, were placed into granaries—large wicker baskets with removable covers. The baskets were around five feet high and three feet in diameter.

Villagers protected their crop from rain and insects by raising the stones off the ground with rocks or tree stumps and covering the outsides in cow manure.

The Bagisu hunted various wild animals for protein, usually small antelope.Hunting was primarily done with a spear, although nets were used on occasion.

During warfare, men used spears and poison tipped arrows. Domestic animals were also kept, although they were rarely used for meat. Every household owned a few cows for dairy and several goats and sheep for trading. Families kept various types of fowl to be eaten on occasion, but they were not fed by the family and were subsequently not well nourished

Ceramics: Pottery was present among the Bagisu. Pots were baked out of clay (lidiri) from riverbeds between the new and full moons. Pregnant women are not allowed near pots while they were being made

Sexual division of production:

Apart from agriculture, there was not much division of labor. Upon marriage, a man gave his wife a field for crops.

This land was cleared and weeded by the man and sowed by the woman; once the crop had matured, men and women worked together to harvest the grain. Conversely, men or women could herd livestock or work as potters. Warfare and construction were among the jobs performed exclusively by males

Inheritance patterns:

Usually, the eldest son inherits his father’s property. This is not guaranteed, however, as the clan can intervene and deprive the son of his privilege. If the son inherits the property, it is his responsibility to provide for his siblings until marriage; using the marriage fees he receives for his sisters to fund his marriage and those of his brothers. Along with taking his father’s property, the son may take his widows as wives.

Political Set-up

The Bagisu had a loose political structure based on clans. Every clan had an elder known as Umwami we sikuka (chief of the clan). These men were chosen on the basis of age and wealth. They were responsible for maintaining law and order, and unity and the continuity of the clan.

They were also responsible for keeping and maintaining the cultural values of the clan and for making sacrifices to the ancestral spirits. Often, stronger chiefs would extend their influence to other clans but no chief managed to subdue other clans into one single political entity. Other important figures in Bugisu included the rainmakers and the sorcerers.

Bagisu/Bamasaba king

Religious belief

The Bagisu worship a supreme God called wele lunya- also known as wele Namanga/Weri Kubumba. According to Naleera (2003: 10-12), namanga is derived from nanga, denoting a cloth, a view indicating that God wears a white cloth to symbolise his ‘holy’ nature. And yet, Khamalwa (2004) notes that wele wemungaki, the God who resides above, is the supreme God of the Bagisu whom the latter consider to be a porter, one who is able to do anything or the one who has power (2004: 22).

Since wele is invisible and resides above, the Bagisu expect him to be everywhere and dwell in every activity they perform including imbalu circumcision rituals. Similarly, the Bagisu believe that everything which takes place comes from him thus respecting wele as much as they can. Wele-lunya has three assistance in performance of some of his duties.Three assistants to wele (called wele lunya) are as follows: wele maina, the one responsible for animal wealth (buhindifu) and is the one who removes barrenness from cows. To appease wele maina, a person sacrifices a barren cow to him in a special shrine.

The priest (normally a diviner) brews beer, blesses it and then sprinkles it over the remaining cows to “remove” barreness from them. There is wele nabende who was responsible for rich crop yields and was in charge of banana plantations.

The Bagisu sacrificed to him by deliberately leaving some bananas to ripen in the banana plantations. Further, wele nabulondela was responsible for births and was symbolised by millet put on the pillar of the house. While brewing beer, the Bagisu keep it under the pole which holds the house in order to allow this deity have her share (see also Turner 1969). When a woman is in labour, she gets hold on the pillar of the house and the Bagisu believe that wele nabulondela is there to help her.

In addition, since millet is used to symbolise this deity, the Bagisu expect the house wife to be as productive as millet and produce as many children as possible. As imbalu (male circumcision) symbolises the second birth, when the boy is brought to the courtyard for circumcision, the mother runs to the house and gets hold on this pillar to symbolise the second birth of her son.

Another deity, wele namakanda was responsible for fertility and was symbolised by the frog. As such, when frogs enter peoples’ homes, they are not supposed to be pushed away since they are believed to bring blessings to the woman of the home to have as many children as possible. Among the Bagisu, people, especially children are forbidden from hitting frogs. It is believed that since frogs “bring” blessings to women to have as many children as possible, hitting them causes the breakage of the back of one’s mother. As such, the mother may not be able to have more children.

Wele is not only responsible for bringing blessings to the people but also inflicting punishments on wrong doers. To do this, the Bagisu believe that God uses small deities among whom is wele matsakha who resides in thickets and is responsible for punishing his victims with sudden illness and fevers. Another dangerous deity is wele lufutu who was responsible for draining blood from people especially pregnant women. Wele lufutu is believed to reside in the river and is symbolised by a rainbow. Whoever could see a rainbow was not supposed to go to the river lest wele lufuutu drains his or her blood.

While wele wanyanga was responsible for causing drought, wele murabula was responsible for breaking the legs of people and animals. Murabula could also cause peoples’ and animals’ eyes to swell and was also appeased around the pillar of the house. Wele kitsali was responsible for causing epidemics like diarrhoea, typhoid, fever, cholera and plagues. A “real” Mugisu man is expected to know how to avoid and also appease these deities.

During the performance of imbalu and other Bagisu rituals, these deities (especially those which are not harmful) must be called upon to come and bless the candidates or persons. In fact, these gods are believed to have power which can make candidates bleed profusely if neglected. The Bagisu believe that next to the gods are the ancestors who also have power to bless or harm people.

Indeed, ancestors are believed to be part of the candidate since the candidates’ name is that of his grandfather or uncle who has recently been part of the human race.

Missionaries introduced the Bagisu to Christianity in the late 1890s. These European immigrants established an “Anglican” system that improved roads and infrastructure, subsequently dividing the area into districts. The Bagisu have been fighting with their neighbors, the Sabei, but the Bagisu tribe is larger and more affluent due to coffee and cotton production.

Passage rituals (birth, death, puberty, seasonal):

Birth: During pregnancy, women did not have to follow food taboos while men must be especially careful to not fall while walking or climbing, as this was thought to cause a miscarriage. After the child was born, the placenta was carefully buried behind the house.

Beer was then poured where the child was born and two trees were planted in front of the house, called mbaga and mwima. For fifteen days after giving birth the wife remained in seclusion, after which she shaved the hair on her head and body and swept the floor of the house.

The gendering process among the Bagisu begins when the child is born and this process is dependent on the sex one acquires at birth. Like in many other African societies, females and males are the only recognized sexes among the Bagisu. In the case where the child is born with both sexes, it is deemed abnormal and society does everything possible to change its sex especially through an operation. When a male child is born, it is called umwana umusinde while a female one is called umukhana.

Female children are called bakhana (plural of umukhana) because they are expected to marry and bring home wealth as soon as they become mature. And yet, males are called basinde (plural form of umusinde) because society expects them to grow and become the custodians of the fathers’ households when the latter grow old . Further, male children are likened to a tree known as lusoola.

As mentioned earlier, a female child among the Bagisu is called umwana umukhana. When it is born, the female is welcomed into society as someone who must bring wealth to the parents when she gets married. As such, she is socialised to become a “good” wife by being associated with activities like making mats, cooking and knitting. To become a “good” woman, girl children are expected to stay near their mothers or aunties and learn “good” eating habits, sitting postures, how to cook and all those behaviours expected of “good” women in society. In fact, a girl who does not behave well exposes her mother to abuses.

The mother is looked at as someone who does not know how to nurture her daughters “properly” and possible suitors may not come to such a home when looking for marriage partners. To make girl children turn into “appropriate” women, the Bagisu also use proverbs such as “bukhwale butuufu intekhelo” (proper marriage is cooking) or “umukhasi umutuufu amanya inda yo museetsa” (a proper woman knows the husband’s stomach). These proverbs are intended to remind the girl that her office in marriage is in the kitchen. She is expected to “maintain” the husband’s stomach.

To demonstrate that cooking is one of the principle tenets of marriage, girls who go for marriage among the Bagisu are said to have gone to “Bufumbo College”, literally meaning she has gone to cook. If a Mugisu man wants to chase away his wife, he begins to occupy the kitchen and cook his own food. A “man” to cook food is abominable, a view which suggests that his wife is worthless.

Bagisu people,Mbale,Uganda

Death:After a death, the body remained in the home until the relatives of the deceased arrived. At sunset, the body was deposited at the nearest “waste ground.” As night fell, horns were blown and the children were told “jackals were coming to eat the dead.”During the night, elderly women related to the deceased went back to the body and cut off pieces for mourning. Over the next three days, relatives mourned in the house and “ate the flesh of the dead.”

Initiation:

Girls: Girls around the ages of 10 or 12 began the process of scarring their faces. Girls would cut the skin on their foreheads and rub ash into the wounds, the product of such actions being ornate keloids. Women could not marry if they hadn’t gone through this process.

Boys: Circumcision seems to have been common practice in the Arabian peninsula in the 4th millennium BCE, while the earliest historical record of circumcision comes from Egypt, dating to about 2400–2300 BCE. Circumcision was done by the Ancient Egyptians possibly for hygienic reasons, but also was part of their obsession with purity. (Mbalu) Boys showing signs of puberty were circumcised in a public ceremony that occurred every two years.

For two to four months prior to the operation, the boys traveled to villages around the clan to receive gifts and dance.

A member of the Bagisu/Bamasaba tribe is carried shoulder high during the launch of the circumcision ceremony at the Imbalu at Mutoto Cultural Grounds outside Mbale town. HUDSON APUNYO/REUTERS

The ceremony occurred two to three days after the arrival of the new moon. At this time, an offering of a fowl was made at the shrine to Weri, the god said to have made the universe, on Mt. Elgon.

The boys were then taken into the forest by the medicine man and the chief—there a goat was sacrificed and the boys covered themselves with the contents of its stomach. After the boys feasted on the goat, they returned to a village where they danced as a group. The boys were taken to the shrine of Weri, blessed, smeared with clay, and told to return to their individual villages for the circumcision.

Imbalu boy by photographer Shannon Jensen.

After having returned to their village, the boys were confronted by an old man that had them each agree to their duties to his clan. Once they agreed, a medicine man removed the boys’ foreskin and all of the skin on their penises, aside from a strip underneath.

After two months of healing, the boys were allowed to join the men in clan councils and marry if they chose to.

Other rituals:

If twins are born: A medicine man offered a fowl to the gods. Three days later, the twins’ heads were shaved and their fingernails were trimmed for inspection. After they had been inspected by the medicine man, the families of the husband and wife feasted together.

If a man committed suicide: His house was broken down and burned. If a wife committed suicide the husband was blamed and he was stripped of his home and possessions.

Murder: If a man murdered someone outside of the clan he had to kill a goat and smear the contents of its stomach on his chest. Until he did this, the man was not allowed to eat food with his hands.

Bagisu people at Mount Elgon

Marriage

However, girls begin to mark their foreheads with keloids at the age of 10 or 12 as a sign of clan membership. As a Bagisu girl is not allowed to marry until she has marked her face, it is probably closely related to the menarche.

A woman could not marry if she hadn’t gone through the initiation rites at the age of 12.

Bride purchase (price), bride service, dowry:

The husband paid a marriage fee to the family of the bride; the father of the groom negotiated the price with the parents of the bride. Usually the fee was three of four cows (but up to ten could be asked for); this was occasionally supplemented with goats. However, the groom provided the family of the bride with other gifts, such as a spear and a hoe, out of custom.

Before the marriage can occur, the groom must pay the marriage fee. After the bride’s family receives the bridal fee, the bride and a number of female companions (as men could not safely cross into another clan’s territory) stayed the night in the groom’s village.

The party returned to their village the next day with a gift of a sheep or a goat. After a feast in her village, the bride returned to the village of her future husband, staying the night in his house with a family member. The next day the family member left and the wife began working in her field. Aside from this tedious process, not formal ceremony or period of seclusion existed.

Imbalu Circumcision Rites

Imbalu circumcision rituals are a religious ritual performance. Like other religious performances, these rituals are associated with spirits and their performance follows strict procedures.

In addition, imbalu circumcision rituals are administered under the unquestionable authority of ritual executors; they involve the evocation of the dead; convenating; and have symbolic meanings which are not known by all the participants.

Cross section of the crowd that turned up for launch of Imbalu at Mutoto Cultural Grounds in Mbale.

The performance of imbalu circumcision rituals is associated with spirits (kimisambwa), which are believed to have come from the clan of Nabarwa, the wife of Masaba who is believed to have lured her husband into getting circumcised.

According to Khamalwa (2004), since all the Bagisu are children of Masaba and Nabarwa, they need to be circumcised in order to avert the spirits of circumcision (kimisambwa kyembalu) from haunting them. It is believed that when the Bagisu had attempted to “abscond” from imbalu, these spirits attacked the male children of Fuuya, thus forcing the Bagisu to revive the circumcision rituals. It has become mandatory that all the Bagisu get circumcised lest spirits of imbalu would haunt them.

To appease these spirits, imbalu candidates are taken to various places to offer sacrifices, Further, imbalu circumcision candidates are smeared with clay from the sacred swamp as a way of putting these candidates in “fellowship” with the spirit of imbalu (kumusambwa kwe mbalu). The swamp where the clay (litosi) is got is sanctified with sacrifices in terms of slaughtered hens and goats in appreciation of the power of the spirits of imbalu.

Furthermore, this spirit is evoked through songs and dances performed in imbalu circumcision rituals. In fact, imbalu candidates are told through song that they should be firm in the spirit of Masaba, the name given to imbalu.

Imbalu circumcision rituals involve the evocation of the dead to come and “witness” as well as bless the candidate. Many informants told me that the Bagisu respect the dead members of their society to the extent that they are referred to as balamu (the “living”). Among the means through which the dead are respected include naming children after them and leaving some food in the cooking pot so that the ancestors may find something to “eat” when they visit at night. Another means of relating to ancestors as the “living” is “calling” them to be “present” during imbalu circumcision rituals.

If these dead people (bakuka ni bakukhu)come on their own during the performance of these rituals, they are believed to cause severe harm to the candidate. So, they must be “invited” through sacrifices, music, and dance so as to make the candidate firm during pen-surgery.

Imbalu is a religious performance since it involves convenanting. It is believed that the blood which is shed as a result of the surgery of the penis is a confirmation to the ancestors that the boy is part and parcel of the society the ancestors left.

An Imbalu candidate is pulled away from clashes with police. There was a skirmish at Mutoto Cultural Grounds when youth forced their way into reserved arena for the cultural performance.

Imbalu Preparatory Stage

The preparatory stage is the first phase in the imbalu cycle, which begins in January till July of an even year, the year of imbalu. The rituals, musics and dances performed in the preparatory stage are intended to announce to the prospective imbalu candidates, their parents and relatives that the year for imbalu rituals has began.

As such, those who are ready to graduate into manhood are expected to come forward and declare their candidature through singing and dancing. Further, during the preparatory stage, imbalu candidates visit distant relations for blessings and to solicit for money and materials that will be are used in the rituals, as well as gifts.

Bagisu Ugandan traditional surgeons display circumcision knives before Mbalu initiation ceremony

The imbalu preparatory stage also involves the reminding ritual (khushebusa imbalu). The primary aim of the reminding ritual is to inform imbalu stakeholders that the year for imbalu has come so as to give them ample time to search for costumes, food and animals which are used to feed people and offer sacrifices (interview, 2009).

And yet, Philip Wamayosi, an elder charged with the role of keeping the reminding drum stressed that khushebusa reminds boys aged between sixteen and twenty- two years about paying the “cultural debt” (interview, January th, 2009). Imbalu as a form of identity must be performed by all the Bagisu. As such, imbalu is also considered a cultural debt, which is an activity every male Mugisu must fulfill in order to be considered a member of the society.

Imbalu boys dancing

Khushebusa imbalu: Reminder about Manhood

Khushebusa is a ritual that reminds prospective imbalu candidates, their parents, relatives and circumcisers that the year is for imbalu. This ritual is performed on 1st January, during the circumcision year and involves sounding a special drum known as ingoma ye khushebusa (the drum that reminds). Ingoma ye khushebusa is a medium size drum of about three feet in length.

It has a double membrane though only one side of this drum is played. The top part of the reminding drum is larger than its bottom. In every clan, there is a special family called babashebusa (those who remind others) charged with the responsibility of keeping and performing the reminding drum.

The custodians of this drum are always aware of the beginning of the circumcision year and the activities it brings with. As such, when this year begins, they play the reminding drum from either their compounds or the village playground to tell people to “wake up” and prepare for imbalu circumcision rituals. Apart from being sounded to remind people about imbalu rituals, the reminding drum is also sounded during last funeral rites, especially the burial of men who produced male children. In fact, men who are circumcised and have produced sons are highly respected among the Bagisu and are accorded “powerful” burial ceremonies when they die. Relating imbalu circumcision rituals to activities like funeral rites establishes that imbalu defines the whole life cycle of a Mugisu.

Usually, the beating of the reminding drum begins at 4:00 O’clock in the morning. This drum is sounded every after six hours until 4:00 O’clock in the evening. Phillip Wamayosi, an elder charged with the custodianship of the reminding drum informed me that sounding the reminding drum begins early in the morning so as to deliver the message to all people. He said that “there are people who may go on journeys. We aim at giving the message when all people are still at home. They go on their businesses when they have heard the message”.

Moreover, at noon is when most people come from their gardens. Wamayosi explained that sounding the reminding drum at noon is aimed at informing people that whatever they may do, imbalu rituals are part and parcel of their programme. Finally, 4:00 O’clock in the evening is a time when most social activities like naming or last funeral rites are performed. And since imbalu is defined as a social activity, the reminding drum is sounded at 4:00 O’clock to inform participants to come out and show the clansmen and women their intentions for imbalu in that year.

The sounding of the reminding drum follows a pattern which depicts clan seniority. A number of informants told me that among the Bagisu, older brothers are the ones to lead younger ones in all aspects of life and this hierarchy must be articulated during the performance of imbalu circumcision rituals. As such, the most senior clan sounds its drum first. Hearing the drum rhythms, the next clan follows until the least senior clan joins. At 4:00 O’clock in the evening, when prospective imbalu candidates hear the reminding drum, they put on thigh bells, headgears and other dancing regalia and go around villages singing and dancing.

Among the songs sang during khushebusa rituals is “Khukana Bushebe.”

The literal translation of the text of the song khukana bushebe is thus:

Shalelo khukana bushebe >> today, we want circumcision

Baseyi Bamasaba khwolile >> Masaba elders, we have come

Imbalu ye Masaba yolile >> Masaba’s imbalu has come

Ni nafe khukana khunjile >> We also want to be circumcised

The candidates then move to village playgrounds or along major roads with other people responding to the songs they sing. The music performed by boys during this period is intended to announce to elders that they are ready for the imbalu circumcision ritual this year. As a matter of fact, this music and dancing are a way of communicating one’s candidature. Indeed, it is after hearing the reminding drum that the prospective candidates come out to portray their candidature through singing and dancing.

Khushebusa ritual is also a “school” for imbalu candidates to learn how to sing and dance imbalu. And since these boys do not have experience aboutmanhood, circumcised men are the ones who lead them in songs and dances. These are men who are skilful in singing, dancing and other societal values. While men inform boys about the role of men in society, they also educate boys on how to relate with other men in society. Such men are known as banamyenya (singular, namyenya).

In his study about imbalu rituals, Khamalwa defines namyenya as “a local poet and historian, adept at composing didactic songs, knowledgeable in the

history of the tribe in general, knows the myths and genealogies of different clans, as well as the legends associated with the different heroes.”

Since he is hoped to impart societal values, including the traits expected of men among the Bagisu, namyenya is charged with the responsibility of leading imbalu circumcision candidates. Among other activities of the khushebusa ritual is the blowing of horns (long and short horns known as tsingombi and tsimbebe, respectively).

Candidates from adjacent ridges blow horns and are answered by their counterparts across the ridge. However, because buffalos are no longer hunted and yet they are the ones where horns are fashioned, horns have drastically reduced from imbalu musical performances. Most informants told me that since imbalu is intended to “turn” boys into “tough”, “aggressive” and “strong” “men”, costumes and props used in these rituals must be made from fierce wild animals. As a matter of fact, the buffalo is considered by the Bagisu to be among the “toughest” and “fiercest” animals. After the khushebusa ritual, imbalu candidates gather and perform isonja dance.

Isonja Dance: A Site for Testing Manhood

Isonja is an imbalu dance performed to train candidates about dancing skills as well as enable them get acclimatized with the items they wear when performing imbalu rituals.

This dance is staged in an open field, normally one preserved for special clan meetings. Isonja dance is performed between the months of January and March since this period is not characterized with a lot of agricultural work. This dance is performed in the evening when candidates, their song and dance instructors, as well as the spectators have finished the day’s work and therefore have time to participate in the dance.

In staging isonja dance, imbalu candidates from a particular clan come together and hire an instructor either from their own village or another place to lead them in songs and dancing skills. Instructors are hired due to their scarcity in many parts of Bugisu; a situation that increases their demand in society.

Prior to the emergence of the “monetary economy”, each imbalu candidate could pay the instructors of isonja dance in terms of eggs, local beer or by physically going to work for them in their gardens. Each imbalu candidate contributes between two and five hundred Ugandan shillings per day for the isonja instructor.

While going to the venue of performing isonja dance, music takes central place. Candidates run to the venue while singing songs they learnt during khushebusa. Candidates “lead” themselves as they move to the performance venues. When they lead themselves, candidates show that they are people who can stand on their own as “men”. When candidates arrive at the performance venue, they stand in a circle and are led by their instructor, nanyenya.

Nanyenya “tutors” imbalu candidates on how to sing, dance and take care of their dancing items- thigh bells, headgears, beads as well as the strips of skin which hang on their backs.

Namyenya takes on the “mantle” of leading imbalu candidates in songs and dancing skills at the dancing venue to test whether these candidates are ready for imbalu or no. According to Makulo, what defines a man among the Bagisu is having “tough” muscles as well as being strong. As such, someone seeking manhood is expected to prove that he is tough through the dancing.

Among the songs namyenya sings while instructing imbalu candidates during isonja dance is entitled Yolele Yolele:

Soloist: Yolele yolele >> it has come, has come

Chorus: I yaya yolele, yolele, iyaya >> sincerely it has come, has come

Soloist: Tsobolele uwakonela >> tell the one who Postponed

Chorus: I yaya yolele, yolele, iyaya >> sincerely it has come

Soloist: Kumukamba yakobole >> tomorrow, it will come

Chorus: I yaya yolele, yolele, iyaya >> sincerely it has com

In the first line of the song, namyenya reminds candidates that the year for imbalu has come. In response, candidates confirm what namyenya tells them by singing “sincerely it has come”. While the song leader changes the text, candidates keep on repeating the same text. This musical form relates to the authority of “men” among the Bagisu. Men have authority and as such, when they talk, their authority must be adhered to.

According to Kanyanya, by reemphasising that “it has come, has come”, imbalu candidates reaffirm their obligation to undergo imbalu (interview, January 18th, 2009). Namyenya tells candidates to go and tell whoever is not circumcised, particularly those who had postponed imbalu that it has come. In fact, namyenya’s last line “tomorrow, it will come” re-echoes the fact that one can never dodge imbalu among the Bagisu.

One of the basic motifs in isonja dance is performed when candidates bend their backsand stamp the ground with their right feet. Then one spreads his arms and moves them from the body (trunk). As he dances, the candidate stamps the ground; each time turning to a different direction.

As a matter of fact, isonja dance is primarily intended to enable imbalu candidates to acquire dancing skills and become “tough” in preparation for the pen-surgery ritual. Further, it enables candidates to get acclimatised to items like thigh bells, a cirlet of wood or ivory on the fore head, and the headgear, all used during different imbalu circumcision rituals.

Other items include wooden circular objects with holes curved in the middle of each object so that the candidate can put his hand in it till it fits at the elbow. All these items are heavy and therefore, need mature, muscular, and strong candidates to carry them. As such, isonja is meant to transform boys into people who are mascular and strong enough to match with the traits used to define men among the Bagisu.

Isonja is indeed a site for testing manhood. Throughout the performance of this dance, traits which the Bagisu associate with men like aggressiveness, strength and persistence are emphasised and imparted.

According to Andrew Mukhwana, a “real” man must be strong because after imbalu rituals, he is expected to become independent. Moreover, a man’s wife and children depend on him for protection. Further, in case of any war, men are the ones called upon to defend the society (interview, January 4th, 2009). As such, for someone to be allowed to undergo imbalu circumcision rituals, he must prove that he is strong while performing isonja dance. Similarly, Heald argues that “[l]ike a warrior, the boy must conquer his fear by convincing himself that he has the strength to overcome an enemy” (1982: 17).

To “perform” strength through isonja dance, imbalu candidates are expected to bend the upper parts of the body and stamp the ground heavily, with their right feet. As one stamps the ground, the arms must protrude outwards from the main body, forming a concave shape with them. This concave shape, which Andrew Mukhwana called “khureka tsingumbo” (“sharpening the arms”) is a posture of protection. Sam Waneroba, aged forty-eight, told me that even in daily life, a man who defends himself is one who builds a wall around his home (interview, 2nd March, 2009). According to Waneroba, such a man protects himself before disaster befalls him. Indeed, performers of isonja dance who do not keep their arms “sharpened” are elbowed out of the dancing circle.

Depending on how one dances, he is either pronounced young or weak by spectators and may be asked by the clansmen to wait for the next season as he matures and grows strong (see also

Khamalwa, 2004: 75).

After composing their songs, candidates practice them as they move and dance on road sides with the peers escorting them. Sometimes, imbalu candidates meet with kadodi drummers to establish how the songs they had learn from namyenya can be enforced by kadodi music. To establish this connection, candidates first sing their lines as the drummers create the accompanying rhythms. The searching for imbalu, as discussed in the following subsection is a stage which ushers candidates to the search for manhood.

Khuwenza Busani: Boy “Searching” for Manhood

Imbalu rituals require a lot of resources in terms of money, food and animals and yet only one’s parents may not be in position to provide everything. As such, the novice needs assistance from other relatives.

There is also need to visit relatives and friends for blessings so as to perform imbalu circumcision rituals successfully. As such, after the performance of isonja dance, imbalu candidates visit distant relatives not only to seek for blessings and material help, but also to announce their intensions of becoming “men”. George Wekoye told me that since imbalu ushers someone into manhood, the prospective candidate is expected to be bold enough to inform others that he needs to become a “man”. According to Wekoye, the boy must announce “it” himself such so as to enable his clanmen know that he is “ripe” for manhood.

Similarly, Heald writes that:

throughout the rituals [,] there is a constant stress by the boy [‘s]

kinsmen and those officiating, that the desire for imbalu can come from

the boy alone. He himself chooses the year in which he will be

circumcised and it is repeatedly said that no one is putting any pressure on

him to undergo the ordeal (1982: 18).

To search for imbaludenotes searching for the “spirit of the Bagisu” and likened it to the Kigisu proverb “khuwenza kumusambwa kweefe” (we search for our spirit). imbalu is “war” and therefore, the boy must mobilize his relations (near and far) to come and stand by his side (see also Heald, 1982). As such, during imbalu rituals, one’s relatives must be visited and told about his candidature. In most cases, the female relations are the ones visited since they moved from their clans and got married in distant places.

And since they are now in “their” own clans, these female relations must be visited well in advance because during the period when smearing, brewing of beer, visiting cultural sites and the cutting rituals are performed, these relatives are also busy with imbalu rituals of their husbands’ relations. In fact, searching for imbalu explains the fact that imbalu rituals are collective as they involve relatives from near and far as well as ancestors.

As they visit these relatives, the boy and his escorts run while singing and dancing. During my childhood, I participated in the activities of searching for imbalu where the song “Masaba Akana Imbalu” (Masaba Wants Imbalu):

Masaba amile i Luteeka ari ngana imbalu >> Masaba came from the land of

Bamboo demanding for imbalu

Neewe kana imbalu Masaba imbalu >> But you demand for imbalu, imbalu Yarafua >> is tough

Imbalu yarafua Masaba, >> imbalu is tough Masaba,

Bakhala bijele >> they cut legs

The song leader (namyenya) announces to the public that Masaba is demanding for imbalu, which literally means manhood. However, he warns Masaba that imbalu is “tough”, very “painful” and it tantamounts to cutting off one’s legs. Namyenya leads the song, telling people how Masaba is demanding for manhood. Members of the escorting team just respond aee, as if asking, “is it?” As Khamalwa explains, [t]he novice carries a long stick whose bark has been peeled off. This stick [,] known as kumukheti [,] is what he waves in the air as he dances … (2004:77).

Apart from the boy leading songs, namyenya also play a significant role in leading songs during the period of searching imbalu. Namyenya is always close to the boy to ensure that he learns other songs which he will sing while going to cultural sites, the maternal clan among other rituals. Sometimes, the boy is escorted by his female relations including his sisters and paternal aunts.

The Bagisu expect men to be at the forefront during all public performances unlike women who are expected to merely follow what men do. Imbalu is a space through which men consolidate their power and as such, roles of leading songs, smearing candidates, brewing beer and circumcising are assigned to men. ……

The Pen-Surgery Stage

After the “search for manhood”, the next stage the “the pen-surgery”, the rituals that climax with the removal of the foreskin from the penis. Indeed, the pen-surgery is the most intense stage in the performance of imbalu rituals and includes the rituals of brewing, smearing, visiting cultural sites and the surgery of the penis.

These rituals are performed during the month of August since this is the month of the first harvest when people usually have enough food to feed candidates, their escorts and ancestors through sacrifices. In addition, the August imbalu rituals are performed for candidates who are commonly known as banabyalo (those who do not attend school).

Before examining the rituals, musics and dances performed during the pen-surgery stage, it is important to note that the performance of imbalu among the Bagisu follows clan seniority. As such, senior clans circumcise their boys before junior ones, to open the imbalu rituals.

To “open” imbalu rituals denotes the fact that boys from Bumutoto, the most senior clan are circumcised first. According to Naleera, though many Bagisu believe that Masaba is the man who introduced imbalu, there was a time when the Bagisu stopped to circumcise. Imbalu was “revived by a Mugisu called Fuuya, son of Mukhama of the Bamutoto clan of Bungokho County.”

Because Bamutoto are associated with the revival of imbalu, they are considered senior and therefore, are the first to circumcise their boys before any other Bagisu. In the beginning of August, the Bugisu Cultural Board, instituted by the Local Councils from Bugisu organises the inauguration of imbalu ceremonies for Bamutoto boys to be circumcised. All the Local Council V Chairpersons of Bududa, Manafwa, Sironko and Mbale Districts as well as Members of Parliament from Bugisu sub- region and other political leaders attend imbalu inauguration rituals.

Another dance performed during imbalu inauguration rituals is tsinyimbaand was presented by candidates from Bubulo East. Tsinyimba is a word used to denote the hand bells candidates use to hit a metal tied around their wrists to create rhythm for dancing.

Unlike isonja dancers who use the feet to stamp the ground, tsinyimba dancers use the upper part of the body to display the basic dance motifs. As they shake their shoulders and heads, candidates spread out their hands. They then shake their heads; moving them to the front and behind. Moving to the pace of nanyenya’s song, candidates finally kneel down while moving their backs up and down (see also Makwa 2005: 69).

After witnessing the dances and musics, the invited guests, are led by Bamutoto elders to witness the circumcision of their children. Since Bamutoto boys “open” imbalu rituals, the courage they display during the operation is significant for all imbalu candidates throughout Bugisu.

Many informants confirmed that it is considered bad luck for the umulala (the one who faces the knife first) to shout or fall down when is being circumcised. Other candidates may follow umulala’s example and yet a “real” man must be firm and endure the pain from the beginning to the end of the pen-surgery. To show cowardice during pen-surgery is a demonstration that the candidate will not withstand the challenges of manhood. As such, when Bamutoto boys display courage during pen-surgery, the Bagisu become confident that all imbalu candidates will be firm and eventually transform into the men society desires.

After the circumcision of Bamutoto boys, other clans circumcise their boys but following their order of seniority (see time table illustrated by Khamalwa 2004: 26). The performance of imbalu circumcision rituals in accordance of clan seniority demonstrates that there are gender differentiations between the various clans in Bugisu. By the fact that the Bamutoto revived imbalu, they consider themselves as “better” men than men from other clans of Bugisu.

Further, in all other clans among the Bagisu, imbalu candidates are arranged according to the age of their fathers. If there are five boys, whose fathers are brothers, it is son of the eldest brother circumcised first. However, before the actual pen-surgery, the rituals of brewing, smearing and visiting cultural sites, as well as maternal clans are performed.

Imbalu candidates dancing the Kadoodi dance at Mutoto Cultural Grounds outside Mbale town on Friday August 3.Smeared with flour and decorated with traditional beads and bungles, the circumcision candidates dance in preparation for circumcision

Khukoya Busera: The brewing of beer

The brewing of beer, done three days before pen-surgery, ushers in the most elaborate rituals performed on imbalu candidates. This ritual is performed both at the home of the candidate’s father and the clan leader where the candidate will be circumcised.

In any of the above venues, the candidate is escorted to the stream to fetch water in a pot, which he carries on bare head. There is symbolism in the water taken directly from the stream and that which people keep in their houses. According to Reuben Wamaniala, an elder charged with smearing candidates with yeast, stream water is preferred because it is running unlike the “static” water kept in one’s house. To usher some one into manhood is ensuring that life is a constant “flow”. To ensure this, the Bagisu collect “flowing” water and use it while performing imbalu circumcision rituals (interview, December 28th, 2009).

When the candidate reaches home, he pours the water in a pot containing roasted dough called tsimuma. The elder then adds more water and places the pot under the pillar of the house (inzeko) for maturation. According to Victor Turner (1969), it is under the pillar of the house that the deity mulabula resides.

Mulabula is connected with reproduction and when a woman is in labour, she gets hold on this pillar in order to give birth. It is believed among the Bagisu that the head of the house must always appease this deity by brewing beer under the place it dwells if his wife is to have normal births. And since imbalu is likened tosecond birth, murabula must be appeased if the boy is to successfully undergo imbalu rituals. Murabula is also evoked to be present so as to bless the boy.

Normally, the beer brewed at the home of the candidate’s father is for clansmen to drink after the operation ritual. On the contrary, the beer brewed at the clan leader’s home is what is known as busera bwe kumwendo (the beer for the gourd). In every clan, there is an elder chosen due to his kindness, firmnessduring his circumcision as well as reproductivity to be in charge of the gourd.

In the gourd, he puts the millet-brewed beer and it is this beer that is sprinkled using the mouth on candidates for evocation of ancestral spirits. Millet is highly considered in the performance of imbalu rituals because it symbolised reproduction.

According to Wekoye, after being circumcised, the Bagisu expect the novices to produce as many children as the millet does (interview, January 29th, 2009). Like in other imbalu rituals, the brewing process is accompanied by music and dance. While going to the clan leader’s home, the candidate and his escorts sing songs depicting the boy’s resolve for the knife.

Khuakha Kamamela: Enforcing Man Traits?

Khuakha kamamela literally means “smearing yeast”. It is a ritual where imbalu circumcision candidates are smeared with yeast, beginning on the evening of the day when candidates brew beer and is repeated every evening up to the day boys are circumcised. This ritual involves putting powdered yeast (kamamela ke buufu) into water and mixing it to form a paste. And then, an elder considered for his kindness, wealthy and “productivity” because he has children- especially males, is chosen to smear the candidate. As he performs his task, he calls upon ancestral spirits to come and bless the candidate. He also tells the candidate to be

firm during circumcision as well as what society expects of him as a man. A number of informants explained to me that the significance of the ritual of smearing candidates with yeast is to remind the candidates about what society expects of “men”.

Further, the ritual of smearing candidates with yeast enhances the definition of “real” men as people who are united, social and respectable in society. The smearing ritual concretizes the Kigisu proverb that “kali atweela

kaluma ligumba” (litrally translated as “the teeth which bites together are the ones which can eat the borne). The above proverb means that men among the Bagisu should be together, united and respect one another in order to fight common enemies. Otherwise how can one man resist an attack alone? As the yeast man gives the above admonitions, the candidate must stay still and listen. He should not shake his body or even twitch an eye as this is interpreted as a sign of fear. Other members of the congregation may supplement on what the yeast man says. After smearing the wet yeast, the yeast man, known as uwakha kamamela, takes

powdered yeast and spreads it on the candidate and repeats what he has said before.

Khubeka Litsune: Female- Father “Making” the Man

Before the candidate is smeared with yeast on the second day, he performs the ritual of shaving off the hair from his head, which is known as khubeka litsune. This ritual is performed by the paternal aunt (senje) chosen because of her good behaviour, kindness and production of children especially males. The Bagisu belief that one’s paternal aunt is more or less his or her father.

As such, the paternal aunt is given the title of female-father (papa mukhasi) and freely calls the mother of her nephews or nieces as “my wife”. After all, the cows she brought home in form of bride price are the ones her brother used on his wife’s bride price. As imbalu is likened to second birth, even the senje can give birth to the boy by “shaving off his boyhood” and prepare him for manhood (Wamayosi, interview th January, 2009).

Furthermore, Wekoye told me that imbalu is a social activity which attracts all relations from various corners. And each of these relations must participate in transforming the boy into manhood. As such, shaving is the occasion “dedicated” to the female- father to give “birth” to her nephew (interview, January 29th, 2009). This occasion also enables the boy to know the significance of his paternal female relations and give them due respect in future

While cutting off the boy’s hair, the paternal aunt evokes ancestral spirits to come and bless him. She also emphasises the fact that the boy should be firm during pen-surgery, get married and produce children as “real” manhood is assessed in terms of the above features.

Ise senje wowo >> I your aunt

Shalelo ingurusokho litsune >> Today, I remove your hair

Ukuma imbalu >> Be firm with imbalu

Uyile umukhasi >> Get a woman

Usaale babana >> Produce children

Umanye basenji, bakoko >> Know your aunts, sisters

Obwo busani bubweene >> That is “real” manhood.

For example, female children take their paternal aunt as their elder sister and can discuss issues of sexuality with her. As a matter of fact, paternal aunts teach their nieces “bed matters” and how to conduct themselves in marriage (see also Tamale, 1999: 18). Likewise, boys can entrust their paternal aunts with secrets about their lovers.

Wanyera told me that in the event that a male child is suspected to be impotent, it is his paternal aunt to “check” to ascertain whether the allegation is true or not (interview, January 18th, 2009).

In fact, the paternal aunt can have sexual intercourse with her brother’s male children if she is to find out about their virility. Similarly, during imbalu rituals, the paternal aunt can persuade her nephew to say whether he is ready for imbalu or not. In other words, the boy may tell his paternal aunt his feelings about imbalu especially if he has some fear for the knife and the aunt can persuade him to withdraw from imbalu.

Like other imbalu rituals, the shaving ritual is punctuated with music and dance. Among the songs sangs sang when the boy’s hair is cut is entitled

“Umusani womweene Ukana” (You Demanded for Manhood Yourself).

Leader: Umusani womweene ukana >> you demanded for manhood yourself

Chorus: >> Aho

Leader. Umusani womweene wokanile: >> You wanted manhood yourself

Chorus: >> Aho

This song is sung by female relations as the paternal aunt shaves the boy’s hair. In the song, the boy is told to be strong during pen-surgery; after all he is the one who demanded for (imbalu) manhood. He is also told to be ready to take on the “mantle” of manhood.

According to George Wekoye whose role is to sprinkle imbalu candidates with beer, by re-emphasising the concept of manhood, female relations tell the candidate to perform the roles expected of a man in society. Among the roles a Mugisu man is expected of is to get married, produce children, sustain the basic needs of a family and welcome other members of the clan to his home.

After the shaving ritual, imbalu candidates are again smeared with yeast and taken around the major roads to sing and dance their way to manhood. They meet candidates from other clans, sing songs which depict their resolve for imbaluas well as confirm their readiness to fulfill the obligations of men in society.

Imbalu candidates from various clans met together and re-affirmed their resolve for the knife. Among the candidates I witnessed was one Wakooba who sang about his ancestry and how he had been “crying” for manhood and his song. Continue here:http://mak.ac.ug/documents/Makfiles/theses/Makwa_Dominic.pdf

About the Author

- kwekudee, Tema, Greater-Accra, Ghana

Source: http://kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com/2013/06/bagisu-bamasaba-people-ugandas-most.html

20 Comment

Manyonge Sam, 2024-03-17 at 8:31 PM

good research

Grace Adamz Eithan, 2022-02-12 at 6:22 PM

I want a sketch drawing of the ceremony please

Thank you.😎🥰

Allan, 2022-01-18 at 5:21 PM

If a man marries a woman who is a mugisu do the also circumcised him, and what happens to the young one produced by the two

Uganda Tourism Center, 2022-02-05 at 6:24 PM

No Circumcision is for the Bagisu only and no one can force you to take it and also your children are under your culture and can not be forced. I also want to add that the writer didn’t do all research therefore there is content here not to believe.

Atika christine, 2021-12-23 at 11:20 AM

Thank you lord

masha george william, 2021-11-12 at 11:47 AM

you deserve credit for the work done. Your article needs improvement. The accuracy accounts are questionable. A real mumasaaba needs to undertake a study into the bamasaaba nation.

Real mugisu, 2021-05-18 at 1:43 PM

UTTER RUBBISH, MAKE UR RESEARCH BEFORE POSTING UR BS, EDIT UR TITLE FIRST OR DELETE …HOW DO YOU TERM PEOPLE FEARSOME , CANNIBALISM AS A CULTURE….

James Kamando, 2021-03-30 at 12:47 AM

You are to be commended for this article , but it is very shallow , you only covered one ritual at length and you forgot about the others ,how about inemba ? it is a dance performed the year after circumcision , perhaps a skimmed through and missed it , how about shikhongo? this is a ritual performed when a man is trying to exorcise barrenness from his family , in my case we had a barren cousin and my father carried out this ritual , the barren woman is made to carry a goat on her back , I remember that either at the start of the journey or at the end of it there is a small grass structure in which a boy and a girl are made to sit in , also the barren woman passes a man wrestling with a snake in a shallow river , how about ingoma ye vafu! it is performed during burial , how about khadodi? it is a dance that accompanies the circumcision in which young girls shake their bottoms , the masaba culture is very rich and it deserves a whole book , not just an article. May be you could write one?

Wakumà Fred, 2020-10-09 at 9:49 PM

Am so much impressed

Thank you

Badru Gidudu Walimbwa, 2020-09-09 at 6:11 PM

Whereas some sections of this article are informative about Bamasaba, i do not agree with certain sections. For, example the claim that some parts of the dead are or were eaten. The author needed to do more focus group discussions.

Pour Femme, 2020-09-05 at 5:55 AM

This is the most adamant article i have ever read, no research, just some nincopoop pushing some propaganda, whoever is the admin for this site should understand this doesnot promote your business in any way , it only shows how a tribalistic lot you are. Sadly you have no actual address, because by the reviews it shows this article is so wrong and needs to be actually edited or pulled down. The title alone 😂😂😂😂

Ralph Masaba, 2019-10-31 at 4:55 AM

Good

Amos Masaba, 2021-09-04 at 7:06 PM

The author’s piece of information was a bit shallow for example, he never included the totems, also ingoma ye khamakhoro/ or magoto as somee dialects call it. This is a ritual dance that was performed by the family of the deceased throughout the funeral especially if the deceased had lived to the very ripe age- magoto; he never talked about the prestigious traditional dish – khamaleya {bamboo shoots}

Please next time better reach out to us for clarified information. I beg to rest my case. Bamasaba butwera…….

MUGUSHA MARTIN, 2015-10-03 at 3:01 PM

I love the culture but let us as Bamasaba enjoy it peacefully in the next coming year. circumcision does not mean we offer our life for sex whenever a beautiful lady come into contact with you because we are loosing the young generation of 25-40 years. This is due to the feel that since the boys are circumcised they are not easily affected by HIV/AIDS.

Vanessa, 2018-03-19 at 10:58 PM

Yes you’re right Martin.

Watuwa Charles Alfred Wabuyele, 2019-06-04 at 12:22 PM

I greatly disagree with the author about cannibalism. As far as I know and being a Mugisu myself cannibalism as a ritual doesn’t exist among the Bagisu. It is even abominable to be referred to as a cannibal. Yes there is a case of a particular clan at Makhoba River near Bukiende led by a man called Makyukani whom it is said used to practice cannibalism and therefore the author needs to check his facts properly before publishing. Even Makyukani’s case was more of mythical whispers than realities because there was no authenticated proof to date.

To correct this author, before the coming of the missionaries, the dead were not buried especially the old men. The body would be kept for about three days or more and it would taken out in the night and placed in the open a distance of about 100 meters for the hyenas to eat. All this happens when the elderly people are keeping watch. Immediately the a bone is hard breaking, people would then run into the houses till the following morning when the skull is collected and placed in between trees stumps of zisoola. This formed a future base for example if a boy was to circumcise, he would be taken to this place to receive blessings on his final journey to face the knife (imbalu).

Other cases about the dead people including children whose spirits were troublesome to their surviving kin had the following performed on them. Such people could have their remains exhumed and scattered in the bushes and banished from causing troubles to the living in ceremonies that involved cleansing of even those who did the actual exhumation.

David Mafabi, 2019-08-10 at 7:48 AM

I think the author did not do enough research on the Bagisu/Bamasaba. He should not have delt with only one source because there are many misrepresentations which i actually dont agree with. He should get back again and do more, we are willing to give him information. Thanks

hafsa, 2021-12-02 at 7:44 PM

Were if all this information is not misinformed then I’m Afraid I might have no future in my Relationship which I have with a Mugisu guy

Masaba,Willy, 2020-12-25 at 6:53 PM

Watuwa, Charles Alfred.

Please mail me. Willy.masaba@yahoo.com

I like reading about my culture and since you have more information to add on, i request to reach you.

Thank you.

Khalayi Victoria, 2025-05-15 at 2:08 PM

so amazing am a gishu bt didn’t know anything meaning baganda came from bagishu(kundu)who feared circumcision and moved to the central 😁🙏